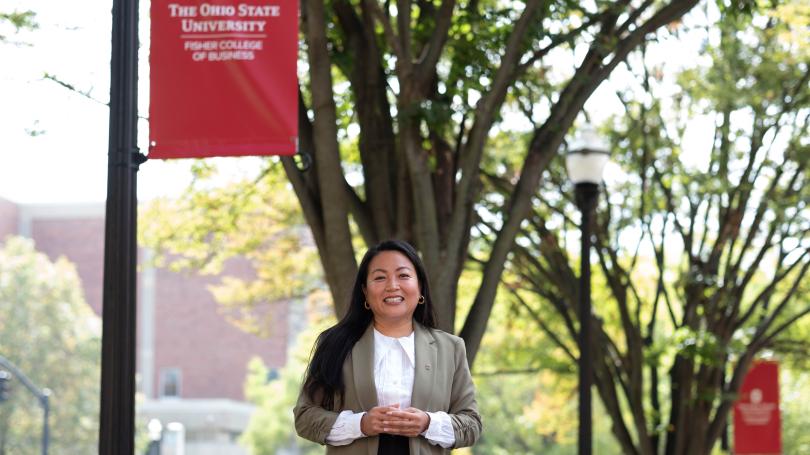

Forging a path toward justice and peace: Sera Koulabdara (BSBA ’07)

As a young teen, Sera Koulabdara loved to walk across The Ohio State University campus with her father. He would point to buildings filled with lecture halls and libraries and talk about his dreams for Sera.

“He would say, ‘This will open doors for you’,” she recalls.

Sera’s father and mother, Sith and Toune Koulabdara, longed to see their four children attend the university in their adopted city. Sera longed to make them proud.

“My parents sacrificed so much,” she says. “They knew that education would give us opportunity.”

Those leisurely campus strolls were a world away from the family’s native Laos, where walks in the Southeast Asian countryside required a very different conversation. Even at six years old, Sera understood her parents’ steadfast rule on those walks: Stay on the well-worn paths and avoid the soft ground on either side; unexploded bombs may lay buried there.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the U.S. wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, a significant milestone for Sera (BSBA ’07). As the CEO of Legacies of War, she advocates and raises funds for communities and survivors impacted by the unexploded ordnance (UXO) left behind after the soldiers and tanks retreated.

The Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit provides education and awareness about the need for continued demining in Southeast Asia, victims assistance and attention to ongoing conflicts in other countries around the world. Sera, who specialized in international business as a student, frequently addresses Congress and United Nations delegations about the human and environmental tolls of war.

An unexpected career change

“I always thought I would be doing international finance, working with venture capitalists to bring business to emerging markets,” says Sera.

Following graduation from Ohio State, she landed a job with Big Media Group in Lommel, Belgium, creating country profiles and advising mostly European companies on where and how to invest. Her first assignment took her to Kuwait in the Middle East and Abu Dhabi and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. Then she traveled to Ghana and Botswana in Africa.

“I spent a lot of time talking to businesses, politicians and local people to determine what would be attractive for companies that wanted to relocate or invest there,” she says.

But it was the experiences and people outside of work that had the greatest impact on her and her career.

“The malls in Abu Dhabi and Dubai had stores like Chanel and Gucci and brands that I could never afford. There was a Starbucks on every corner and coffee was $15 in 2010,” she says.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was the man from the Philippines who worked in her hotel and regularly sent his $80 monthly paycheck home to his family. In Africa, where Sera had a car and a driver, children approached her for money for food.

“I was making a lot of money for a 20-something out of college, but I saw so many injustices, and I wanted to do something,” she says.

She looked for an opportunity to do volunteer work in Africa and found it in the Clinton Foundation’s clean water initiative in West Africa. That work ultimately charted the course for her next steps into the nonprofit world.

“When my contract [with Big Media Group] was ending, they gave me two weeks to go home and think about renewing it,” she says. “I thought I could do something different, either go back to school, work for USAID or maybe look at a nonprofit.”

She remembered being part of an after-school program at the United Way, so she visited the Central Ohio chapter. She eventually became their relationship manager responsible for fundraising. From there, she served as development officer for the Make-A-Wish Foundation and director of the Heart Walk for the American Heart Association.

At the same time, her older brother, Bay (BS ’05), an architect living in Washington, D.C., had been volunteering with Legacies of War and introduced his sister to the organization and its mission.

Career and culture come together

Sera’s parents rarely talked about their experiences during the war in Laos.

“I started reading more about the history, combed the Legacies of War website and learned everything my parents had been shielding us from,” she says.

Between 1964 and 1973, the United States dropped more than two million tons of bombs on Laos during what became known as the Secret War, a covert bombing campaign waged by the CIA to destroy communist supply lines between Laos and Vietnam.

The number of bombs dropped was equivalent to a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years, says Sera.

In total, more than 13 million tons of ordnance was dropped on Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam during the war, contaminating farmland and posing a danger to residents of all three countries to this day.

“Of the bombs dropped in Laos, about 30 percent failed to detonate,” says Sera. “The ground in Laos is very soft, and the bombs would stay in the ground and become dormant. They can still explode 50 years later.”

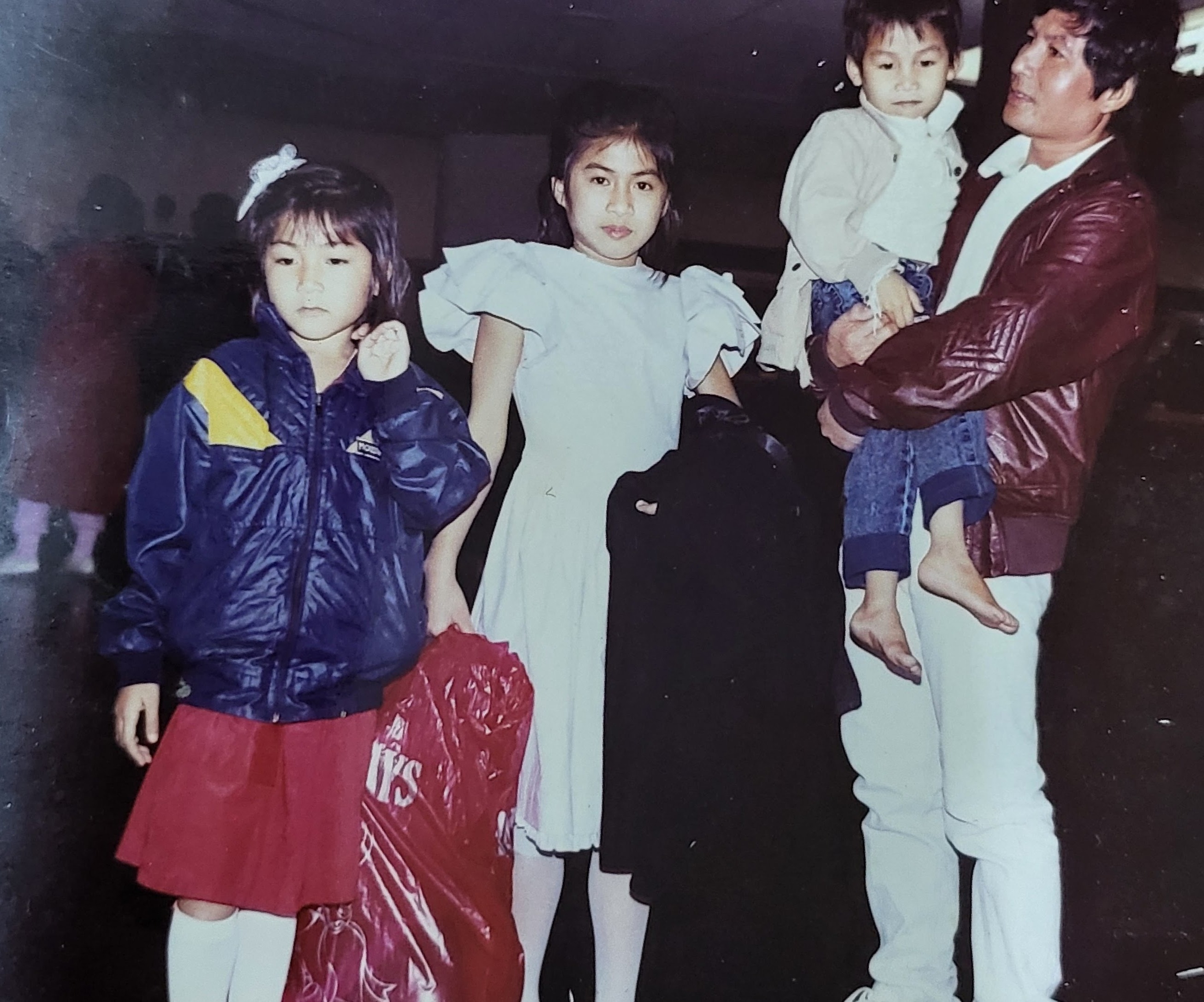

That reality prompted her parents to move to the United States in 1990, when Sera was six years old. Her father, a respected surgeon in Laos, frequently treated farmers and residents who lost limbs and their lives to the once-dormant explosives. After he had to amputate the leg of one of Sera’s young classmates who mistook a bomb for a toy, her parents made the decision to flee.

The Koulabdaras connected with cousins in Nebraska, Illinois and Virginia, before eventually making their home in Columbus, where the diaspora community from Laos was growing. Her father, unable to practice medicine in the United States, worked odd jobs. Her mother, a gifted seamstress, did alterations and boxed donuts at a Krispy Kreme.

At the time, Sera wasn’t fully aware of the sacrifices her parents had made.

“They said the war was in the past, let’s focus on the future,” she says.

In her quest for more information about the war and its aftermath, Sera reached out to the Legacies of War founder, Channapha Khamvongsa, who had fled Laos with her own family as a child and established the organization in 2004.

The two shared family stories and a deep love for their country and culture.

“As the years progressed, I started doing more volunteer work, fundraised for the organization and spoke to members of Congress,” says Sera.

She ultimately became a member of the Legacies of War Board of Directors and was hired as executive director in 2019 when Channapha retired. In 2023, Sera was named CEO.

She divides her time between Columbus and Washington. She regularly travels with delegations to Laos and more recently to Ukraine, where the country’s ongoing conflict with Russia escalated in 2022.

She has visited 23 cities and traveled over 3,000 miles in Ukraine, talking to farmers who lost their farms and assessing the level of soil contamination from explosives.

“The war impacts the United States because we also depend on crops from Ukraine,” she says. “Detonated bombs will ultimately come back to us in our food supply.”

Legacies of War has two staff, including Sera, an occasional college intern and a large contingency of volunteers.

“We operate on a shoestring budget of $350,000, but we do so much because we are truly volunteer-led,” she says. “We’re able to do what we do because of people who have a passion for war-impacted communities.”

Under Sera’s leadership, Legacies of War has secured $264 million for humanitarian demining and earned bipartisan support in Congress. The organization does not receive government funding, so the bulk of their income is donor-provided.

“Most people don’t know about the war, but when they hear there are still children being killed by bombs, they want to do something,” she says.

Sera is also the chair of the U.S. Campaign to Ban Landmines and Cluster Munition Coalition, co-chair of the War Legacies Working Group and a founding member of the Global Leadership Council, an international network of experts in leadership and organizational transformation.

This year, she was named a 2025-26 delegate to the U.S.-Japan Leadership Program, a collaborative network of business and government leaders, philanthropists, educators and artists. They traveled together to Japan and visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum on the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Considered an expert in mine action and advocacy, Sera has been featured in USA Today, The New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, NBC and more. In honor of the International Day of Peace in September, she wrote a column for USA Today about the human cost of war and the need for disarmament in Ukraine.

“Disarmament must extend beyond the absence of nuclear weapons,” she wrote. “It must include cleaning up deadly remnants of war, restoring ecosystems and supporting communities that have been harmed. Humanitarian demining, chemical remediation and environmental recovery are all essential forms of post-war justice.”

A legacy remembered and a promise kept

A recent visit to Ohio State and Fisher stirred unexpected emotions for Sera. She recalled those walks with her father, who passed away in 2017, the professors who encouraged her and the dreams of a young girl from Laos who had longed to make her parents proud.

A gifted student and valedictorian of her high school class, Sera received the prestigious Academic Excellence for Asian Americans scholarship to attend Ohio State. She studied business because she enjoyed math and excelled at reading and writing.

“Business really resonated with me,” she says. “I like order and structure and that is what Fisher offered.”

At Fisher, she co-founded a Southeast Asian student organization and engaged her professors in discussions about law and finance. She landed her first job with the help of a teaching assistant who provided sound advice and helpful connections.

She now strives to be that kind of mentor to the Legacies of War interns. She often tells them what she would tell her 21-year-old self: “Ask for what you want — exactly what you want — and what you deserve.”

She wants women, especially, to know their value in the field and in the boardroom.

“I want young women to know they can be in the room with men and talk about bombs,” she says. “Developing a generation of women in mine action is a huge priority for me because women bring heart to it.”

The same heart her parents brought to their community and their family.

Shortly before his death, Sera’s father finally talked about the war. He told his children how at age 14 he hid in caves in the jungle while the bombs fell outside.

“In many ways, I knew our conversation brought up something he probably wanted to forget, but on his deathbed, he wanted to be unburdened by all the trauma he saw,” she says.

“My parents always found a way to enrich our lives and teach us what matters most: what you leave behind is much more important than what you take with you. It’s about service to your fellow community.”

"My parents always found a way to enrich our lives and teach us what matters most: what you leave behind is more important than what you take with you."